In this state where

natural habitats have been all but obliterated through conversion to cropland,

Iowa's endangered species legislation has a vital role to play. However, the

information pertaining to rare species legislation comprises a relatively extensive and complex data set

that is largely inaccessible because the sources are government publications,

unpublished reports and professional correspondence. The

rare species legislation comprises a relatively extensive and complex data set

that is largely inaccessible because the sources are government publications,

unpublished reports and professional correspondence. The  purpose

of this website and database is to make these data readily available in an interactive

format and to include background information that provides a useful context

for evaluating revisions of the endangered and threatened plant species list

when they are proposed. A second phase of this project is underway and involves

development of a database of all the University of Iowa Herbarium Iowa collections'

data, particularly distributional information, and to make these available in

an interactive format that will include county range maps.

purpose

of this website and database is to make these data readily available in an interactive

format and to include background information that provides a useful context

for evaluating revisions of the endangered and threatened plant species list

when they are proposed. A second phase of this project is underway and involves

development of a database of all the University of Iowa Herbarium Iowa collections'

data, particularly distributional information, and to make these available in

an interactive format that will include county range maps.

The database is a compilation of information on rare Iowa plants from four sources. These sources include (see Literature Cited for bibliographic details):

• five Iowa Administrative Code lists of endangered and threatened plant species (Iowa Administrative Code 1977, 1984, 1986, 1988, 1994)

• 1998 list proposed to supercede the 1994 Iowa Administrative Code list (J. Pearson, Iowa DNR (Department of Natural Resources), in litt. 1998)

• 1998 candidate list (J. Pearson, Iowa DNR, in litt. 1998)

• lists from three endangered and threatened plant reports (Roosa & Eilers 1978, Roosa, Pusateri & Eilers 1986, and Roosa, Leoschke & Eilers 1989)

Five groups of plants/plant-like organisms -- vascular plants ('higher' plants), mosses, hepatics (liverworts), lichens, and fungi (mushrooms/toadstools) -- are included in the database; however, most of the data pertain to vascular plants, which is the only group included in the Iowa Administrative Code lists of endangered and threatened plants. Organized by plant/plant-like group, the data include:

• Latin species name according to source (see above). Source names are abbreviated as follows: Iowa Administrative Code (IA Adm. Code), proposed list of 1998 (DNR Prop. List 1998), candidate list of 1998 (DNR Cand. List 1998), and reports on endangered and threatened

plants (E & T Report).

• Latin family name according to Eilers and Roosa (1994), The Vascular Plants of Iowa. If the family name in Kartesz (1999), A Synonymized Checklist and Atlas with Biological Attributes for the Vascular Flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland, is different, it is included in brackets.

• common name according to Eilers and Roosa (1994), and also Gleason and Cronquist (1991) ), Manual of Vascular Plants of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, and Kartesz (1999), if the latter two differ from Eilers and Roosa.

• category (e.g., endangered, threatened, special concern, extirpated) assigned in each source (Iowa Administrative Code lists, 1998 proposed list, 1998 candidate list, and reports on endangered and threatened plants).

• Latin species name accepted by Eilers and Roosa (1994)

• Latin species name accepted by Gleason and Cronquist (1991)

• Latin species name accepted by Kartesz (1999)

• Latin species name according to source

• Latin family name according to Anderson, Crum and Buck (1990), List of the mosses of North America north of Mexico, and Anderson (1990), A checklist of Sphagnum in North America north of Mexico.

• category assigned in 1998 proposed and candidate lists.

• Latin species name accepted by Anderson, Crum and Buck (1990) and Anderson (1990), except in a few instances when more recent taxonomic and nomenclatural changes have been incorporated.

• Latin species name according to source

• Latin family according to Stotler and Crandall-Stotler (1977), A checklist of the liverworts and hornworts of North America.

• category assigned in 1998 proposed and candidate lists.

• Latin species name accepted by Stotler and Crandall-Stotler (1977)

• Latin species name according to source

• category assigned in 1998 proposed and candidate lists.

• Latin species name accepted by Esslinger and Egan (1995)

•Latin species name according to source

• Latin family according to Miller and Farr (1975), An index of the common fungi of North America.

• category assigned in 1998 proposed and candidate lists.

• Latin species name accepted by Miller and Farr (1975)

The

tables below summarize data in five Iowa Administrative Code lists of endangered

and threatened plant species (IA Adm. Code 1977, 1984, 1986, 1988, 1994), a

1998 list proposed by the Iowa DNR (Department of Natural Resources) to supercede

the 1994 Iowa Administrative Code list (DNR Prop. List 1998), a 1998 candidate

list by the Iowa DNR (DNR Cand. List 1998), and lists from three endangered

and threatened plant reports (E & T Report 1978, 1986, 1989). Category abbreviations

(e.g., E for endangered, T for threatened, SC for special concern, X for extirpated,

etc.) correspond to those in the database.

The

tables below summarize data in five Iowa Administrative Code lists of endangered

and threatened plant species (IA Adm. Code 1977, 1984, 1986, 1988, 1994), a

1998 list proposed by the Iowa DNR (Department of Natural Resources) to supercede

the 1994 Iowa Administrative Code list (DNR Prop. List 1998), a 1998 candidate

list by the Iowa DNR (DNR Cand. List 1998), and lists from three endangered

and threatened plant reports (E & T Report 1978, 1986, 1989). Category abbreviations

(e.g., E for endangered, T for threatened, SC for special concern, X for extirpated,

etc.) correspond to those in the database.

|

SOURCE & YEAR CATEGORY |

IA

Adm. Code 1977 |

E

& T Report 1978

|

IA

Adm. Code 1984

|

IA

Adm. Code 1986

|

E

& T Report 1986

|

IA

Adm. Code 1988

|

E

& T Report 1989

|

IA

Adm. Code 1994

|

DNR

Prop.

List 1998 |

DNR

Cand. List 1998 |

| Endangered (E) |

100

|

101

|

123

|

123

|

123

|

140

|

137

|

64

|

16

|

|

| Threatened (T) |

52

|

51

|

56

|

56

|

56

|

58

|

58

|

89

|

93

|

|

| Special Concern (SC) |

|

|

|

|

33

|

28

|

29

|

227

|

167

|

|

|

Extirpated

(X) |

|

69

|

|

|

49

|

|

45

|

|

|

|

| Undetermined (UnD) |

|

25

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Candidate Species (C) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

538

|

| TOTAL E + T |

152

|

152

|

179

|

179

|

179

|

198

|

195

|

153

|

109

|

|

| TOTAL E + T + X |

|

221

|

|

|

228

|

|

240

|

|

|

|

|

SOURCE & YEAR CATEGORY |

IA

Adm. Code 1977 |

E

& T Report 1978

|

IA

Adm. Code 1984

|

IA

Adm. Code 1986

|

E

& T Report 1986

|

IA

Adm. Code 1988

|

E

& T Report 1989

|

IA

Adm. Code 1994

|

DNR

Prop.

List 1998 |

DNR

Cand. List 1998 |

| Endangered (E) |

3

|

|

||||||||

| Threatened (T) |

25

|

|

||||||||

| Special Concern (SC) |

28

|

|

||||||||

|

Extirpated (X) (incl. Presumed Extirpated, PsX, and Possibly Extirpated, PoX) |

|

|

||||||||

| Undetermined (UnD) |

|

|

||||||||

| Candidate Species (C) |

|

135

|

||||||||

| TOTAL E + T |

28

|

|

||||||||

| TOTAL E + T + X |

|

SOURCE & YEAR CATEGORY |

IA

Adm. Code 1977 |

E

& T Report 1978

|

IA

Adm. Code 1984

|

IA

Adm. Code 1986

|

E

& T Report 1986

|

IA

Adm. Code 1988

|

E

& T Report 1989

|

IA

Adm. Code 1994

|

DNR

Prop.

List 1998 |

DNR

Cand. List 1998 |

| Endangered (E) | 0 | |||||||||

| Threatened (T) | 7 | |||||||||

| Special Concern (SC) | 6 | |||||||||

|

Extirpated

(X) |

||||||||||

| Undetermined (UnD) | ||||||||||

| Candidate Species (C) | 32 | |||||||||

| TOTAL E + T | 7 | |||||||||

| TOTAL E + T + X |

|

SOURCE & YEAR CATEGORY |

IA

Adm. Code 1977 |

E

& T Report 1978

|

IA

Adm. Code 1984

|

IA

Adm. Code 1986

|

E

& T Report 1986

|

IA

Adm. Code 1988

|

E

& T Report 1989

|

IA

Adm. Code 1994

|

DNR

Prop.

List 1998 |

DNR

Cand. List 1998 |

| Endangered (E) |

0 |

|||||||||

| Threatened (T) |

0 |

|||||||||

| Special Concern (SC) |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Extirpated

(X) |

||||||||||

| Undetermined (UnD) | ||||||||||

| Candidate Species (C) |

1 |

|||||||||

| TOTAL E + T |

0 |

|||||||||

| TOTAL E + T + X |

|

SOURCE & YEAR CATEGORY |

IA

Adm. Code 1977 |

E

& T Report 1978

|

IA

Adm. Code 1984

|

IA

Adm. Code 1986

|

E

& T Report 1986

|

IA

Adm. Code 1988

|

E

& T Report 1989

|

IA

Adm. Code 1994

|

DNR

Prop.

List 1998 |

DNR

Cand. List 1998 |

| Endangered (E) | 0 | |||||||||

| Threatened (T) | 0 | |||||||||

| Special Concern (SC) | 3 | |||||||||

|

Extirpated (X) (incl. Presumed Extirpated, PsX, and Possibly Extirpated,PoX) |

||||||||||

| Undetermined (UnD) | ||||||||||

| Candidate Species (C) | 3 | |||||||||

| TOTAL E + T | 0 | |||||||||

| TOTAL

E + T + X |

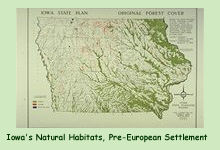

One frequently hears

the assertion that 'Iowa is the most altered state in the union', in reference

to the devastation of natural habitats since the time of European settlement.

The validity of this statement is evident at a glance on the NRCS

(Natural Resources Conservation Service) map showing Percent of Non-Federal

Area in Cropland. Only Illinois, and perhaps Indiana, rival Iowa in the areal

extent of cropland. In Iowa, estimates are that less than one-tenth of one percent

of the tallgrass prairie (and virtually none of the savanna) that covered approximately

83% of the landscape remains today1.

Similarly, less than three-tenths of a percent of the natural wetlands that

comprised perhaps 6% of the surface area remain2.

On the surface, the forests appear to have fared  somewhat

better, with approximately fifty percent of the original surface area of 11%

still wooded3; however, this

figure is misleading since much, if not most, of the natural forests have been

altered by logging and other management activities. Analyses of 1998 Landsat

images by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources Geological Survey Bureau

(ftp://ftp.igsb.uiowa.edu/pub/download/

somewhat

better, with approximately fifty percent of the original surface area of 11%

still wooded3; however, this

figure is misleading since much, if not most, of the natural forests have been

altered by logging and other management activities. Analyses of 1998 Landsat

images by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources Geological Survey Bureau

(ftp://ftp.igsb.uiowa.edu/pub/download/

land_cover/cntytot.xls)

reveals that 60% of today's dramatically altered Iowa landscape is comprised

of row crops; 31% is pastures/lawns; and 2% is roads/buildings. Manmade wetlands

comprise approximately .3% of the surface area4.

European settlement marks the beginning of wholesale habitat destruction in Iowa, and also the initiation of alien species introductions. Naturalized alien species, that is, ones that have escaped from cultivation and invaded natural habitats where they wreak havoc on remnants of natural vegetation, are probably as great a threat to native species diversity as habitat destruction. Notable examples in Iowa presently include Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata (Bieb.) Cavara & Grande), Leafy Spurge (Euphorbia esula L.), and Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria L.), three species that are decimating the native species in woodland, prairie and wetland habitats, respectively. According to Eilers and Roosa (1994), 1,958 species of vascular plants have been recorded from Iowa; however, 442 of these are alien, while 1,516 are native. Lewis (1998) noted that 54 additional species have been recorded since the publication of Eilers and Roosa's checklist (Eilers & Roosa 1994), of which eight are alien and 46 are indigenous. More recently, another 39 alien and 12 indigenous species were recorded (Norris et al. 2001). In addition, there are a few more unpublished records (e.g., Horton, Cady and Madsen, unpublished data). Updating Eilers and Roosa's (1994) figures, the current flora is over 2,063 species, of which 489 are alien and 1,574 native. Thus, 24 percent of the species recorded from Iowa are not native. Kartesz' (1999) total of 2,059 species is very close; however, his figure of 405 alien species is slightly lower, but even so, 20 percent are alien. Either way, one-fifth to one-quarter of the plants recorded from this state are naturalized alien species, some of which are having a dramatic, detrimental impact on populations of native species.

Based on Kartesz' (1999) figures, Iowa's native flora (1,654 species) is slightly larger than those of North and South Dakota, and Nebraska (1191, 1486 and 1496 species, respectively), slightly smaller than Minnesota, Wisconsin and Kansas (1840, 1908 and 1794, respectively), and quite a bit smaller than Illinois and Missouri (2313 and 2136, respectively). However, on the basis of surface area, Wisconsin is slightly smaller than Iowa, Illinois is slightly larger, and larger still are Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas and Minnesota (from smallest to largest). Obviously, floristic diversity reflects other factors in addition to surface area. The two that probably have had the greatest impact are physiography, the contours of the land, and phytogeography, the ecological and historical factors that have shaped the vegetation.

Undoubtedly, Iowa's

floristic diversity is influenced by the diversity of landform regions documented

by Prior (1991), and particularly by the physiographic complexity of the Paleozoic

Plateau in the northeastern part of the state and the Loess Hills in the west.

Phytogeographically, Iowa is in a  transition

zone, the ecotone between deciduous forest and prairie, so both eastern and

western elements reach the edges of their ranges here. In addition, boreal/northern

hardwoods elements extend into the state, particularly in the Paleozoic Plateau,

where the cold air (algific talus) slopes provide cooler microsites. Eilers

and Roosa (1994) recognized these same elements and also an Ozarkian woodland

element. With the data in Kartesz and Meacham's Synthesis of the North America

Flora (1999), it is possible to quantitatively analyze the affinities of the

Iowa vascular plant flora relative to that of each state and province in North

America north of Mexico. The similarity ranks on the accompanying map represent

simplified Sørensen similarity indices5

transition

zone, the ecotone between deciduous forest and prairie, so both eastern and

western elements reach the edges of their ranges here. In addition, boreal/northern

hardwoods elements extend into the state, particularly in the Paleozoic Plateau,

where the cold air (algific talus) slopes provide cooler microsites. Eilers

and Roosa (1994) recognized these same elements and also an Ozarkian woodland

element. With the data in Kartesz and Meacham's Synthesis of the North America

Flora (1999), it is possible to quantitatively analyze the affinities of the

Iowa vascular plant flora relative to that of each state and province in North

America north of Mexico. The similarity ranks on the accompanying map represent

simplified Sørensen similarity indices5 calculated from data in Kartesz and Meacham (1999). Floras with the greatest

number of species in common with Iowa have lower numbers and are shaded darker,

while those with fewer species in common have higher numbers and lighter shading.

As one might expect, the floras of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois are most

similar to that of Iowa, but Indiana is equally similar, while Missouri and

Nebraska are no more so than Ohio and Michigan. At the next level (similarity

rank of three), Kansas is no more similar than Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut

and Ontario, while North and South Dakota are less similar still and equivalent

to Kentucky, West Virginia, New Jersey and Massachusetts. Clearly, the strongest

affinities of the Iowa flora are to the east and northeast, with strong similarities

extending as far as the eastern seaboard. In contrast, there is a relatively

abrupt decrease in similarity to the west in Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and

New Mexico, and this decline is much greater than that to the south and southeast,

where, with the exception of Florida, even the states from Louisiana to North

Carolina have higher levels of similarity than western states that are much

closer geographically.

calculated from data in Kartesz and Meacham (1999). Floras with the greatest

number of species in common with Iowa have lower numbers and are shaded darker,

while those with fewer species in common have higher numbers and lighter shading.

As one might expect, the floras of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois are most

similar to that of Iowa, but Indiana is equally similar, while Missouri and

Nebraska are no more so than Ohio and Michigan. At the next level (similarity

rank of three), Kansas is no more similar than Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut

and Ontario, while North and South Dakota are less similar still and equivalent

to Kentucky, West Virginia, New Jersey and Massachusetts. Clearly, the strongest

affinities of the Iowa flora are to the east and northeast, with strong similarities

extending as far as the eastern seaboard. In contrast, there is a relatively

abrupt decrease in similarity to the west in Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and

New Mexico, and this decline is much greater than that to the south and southeast,

where, with the exception of Florida, even the states from Louisiana to North

Carolina have higher levels of similarity than western states that are much

closer geographically.

Considering that Iowa

lies on the eastern border of the Great Plains, and historically over 80 percent

of the surface area of the state was prairie, it is noteworthy that the strongest

floristic similarities are  with

states that were dominated by deciduous and boreal/northern hardwoods forest.

Almost certainly, these latter elements account, in great part, for the relative

richness of the Iowa flora by comparison to North and South Dakota, and Nebraska,

even though these states have a greater surface area. In addition, a significant

number of the species that are largely restricted (in Iowa) to the Driftless

Area in northeastern Iowa also are among the rarest species in the state (see

maps in Pusateri, Roosa and Farrar, 1993). Thus, these boreal/northern hardwoods

forest elements may account for a significant proportion of the historically

rare species recorded from Iowa.

with

states that were dominated by deciduous and boreal/northern hardwoods forest.

Almost certainly, these latter elements account, in great part, for the relative

richness of the Iowa flora by comparison to North and South Dakota, and Nebraska,

even though these states have a greater surface area. In addition, a significant

number of the species that are largely restricted (in Iowa) to the Driftless

Area in northeastern Iowa also are among the rarest species in the state (see

maps in Pusateri, Roosa and Farrar, 1993). Thus, these boreal/northern hardwoods

forest elements may account for a significant proportion of the historically

rare species recorded from Iowa.

In the reports on

Endangered and Threatened Vascular Plants (Roosa & Eilers 1978, Roosa et al.

1986, and Roosa et al. 1989), 91 species are listed as either extirpated,

presumed or possibly extirpated, although extant populations of some of these

have been found subsequently. It is apparent that a significant number of plants

would have been rare in Iowa historically simply because of the phytogeographic

position of

presumed or possibly extirpated, although extant populations of some of these

have been found subsequently. It is apparent that a significant number of plants

would have been rare in Iowa historically simply because of the phytogeographic

position of the state. However, the impact of habitat destruction and naturalized alien

species has ensured that naturally rare species have become even rarer. For

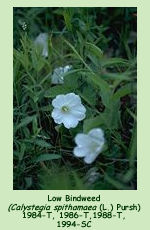

example, Low Bindweed (Calystegia spithamea (L.) Pursh) has been recorded

from nine counties, but only four of these are based on post-1950 records (Roosa,

Leoschke and Eilers 1989). And some surely have been extirpated, for example,

Pod Grass (Scheuchzeria palustris L. var. americana Fern.). Given

the on-going urban sprawl into rural areas, if we are to preserve the dwindling

biodiversity and remnants of natural habitats that represent the natural heritage

of this state, it is vital that effective legal protection be provided.

the state. However, the impact of habitat destruction and naturalized alien

species has ensured that naturally rare species have become even rarer. For

example, Low Bindweed (Calystegia spithamea (L.) Pursh) has been recorded

from nine counties, but only four of these are based on post-1950 records (Roosa,

Leoschke and Eilers 1989). And some surely have been extirpated, for example,

Pod Grass (Scheuchzeria palustris L. var. americana Fern.). Given

the on-going urban sprawl into rural areas, if we are to preserve the dwindling

biodiversity and remnants of natural habitats that represent the natural heritage

of this state, it is vital that effective legal protection be provided.

Herbarium

specimens. Scientists and knowledgeable laypersons preserve collections

(samples) of living plants and these are maintained in repositories called herbaria

(e.g., the University of Iowa Herbarium was such a repository).  Each

specimen is labelled with the locality where it was collected and serves as

a permanent record of the occurrence of that species at a particular site and

point in time. Since each specimen documents a single site, it is necessary

to collect one at each locality where the species occurs. Collections make it

possible to re-evaluate the data (records of the occurrence of species) at any

time by examining a specimen. If a record is based solely on a verbal or written

communication, it is impossible to determine whether that record is valid, i.e.,

whether the identification is correct. In most instances, even a photographic

record is insufficient documentation simply because many characters useful for

identification are too small to be decipherable (or are obscured) in a photograph

or they require accurate measurements that are impossible to obtain from a photograph.

Thus, collections are the vital link with the natural world and they provide

a sound, scientific foundation for all decisions regarding rare species.

Each

specimen is labelled with the locality where it was collected and serves as

a permanent record of the occurrence of that species at a particular site and

point in time. Since each specimen documents a single site, it is necessary

to collect one at each locality where the species occurs. Collections make it

possible to re-evaluate the data (records of the occurrence of species) at any

time by examining a specimen. If a record is based solely on a verbal or written

communication, it is impossible to determine whether that record is valid, i.e.,

whether the identification is correct. In most instances, even a photographic

record is insufficient documentation simply because many characters useful for

identification are too small to be decipherable (or are obscured) in a photograph

or they require accurate measurements that are impossible to obtain from a photograph.

Thus, collections are the vital link with the natural world and they provide

a sound, scientific foundation for all decisions regarding rare species.

The need for collections

presents a conundrum. Are the species we want to preserve going to become even

rarer as a result of documenting their occurrence with collections? First, specimens

of state (and federal) listed species cannot be taken legally without a Scientific

Collector's Permit issued by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources. Beyond

that, specimens of rare species should not be collected without careful investigation of the size of the population and making sure

the site has not been documented already by another investigator. Size of the

population is a judgement call, and it also can be a complicated issue with

plants. For one thing, populations of some plants fluctuate markedly from year

to year. Also, what appears to be a reasonably large population, for example,

one comprised of perhaps 100 individuals, may actually represent just a few

genetic individuals because multiple plants are connected below-ground. Another

consideration is whether the plant is an annual or perennial. If it is an annual,

the long-term impact of removing a plant is less than if it is a perennial because

the annual will die at the end of the growing season. Ordinarily, plant specimens

should include the entire plant, roots and all; however, the destructive effects

of making a collection of a rare, perennial plant can be mitigated by removing

only the above-ground parts, because some plants can regenerate from the roots

the following year.

without careful investigation of the size of the population and making sure

the site has not been documented already by another investigator. Size of the

population is a judgement call, and it also can be a complicated issue with

plants. For one thing, populations of some plants fluctuate markedly from year

to year. Also, what appears to be a reasonably large population, for example,

one comprised of perhaps 100 individuals, may actually represent just a few

genetic individuals because multiple plants are connected below-ground. Another

consideration is whether the plant is an annual or perennial. If it is an annual,

the long-term impact of removing a plant is less than if it is a perennial because

the annual will die at the end of the growing season. Ordinarily, plant specimens

should include the entire plant, roots and all; however, the destructive effects

of making a collection of a rare, perennial plant can be mitigated by removing

only the above-ground parts, because some plants can regenerate from the roots

the following year.

Humans are one of

10 to 100 million species that inhabit the earth (Wilson 1992). Fewer than two

million species have been described and we know virtually nothing beyond the

names of most of those already documented, nothing of the potential economic

and medical benefits they might provide (Wilson 1992).  While

most North American species of plants have been described, even in a state as

small as Iowa and with as few natural habitats remaining, we still are finding

previously undescribed species (albeit rarely), new state records for some (e.g.,

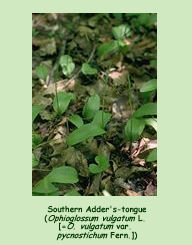

a population of Southern Adder's-tongue (Ophioglossum vulgatum L.) was

discovered in southeast Iowa in 1994, Horton unpublished data), and county records

for numerous species. And we have much to learn about the ecological role of

the species that occur here. The remnants of natural habitats and the biodiversity

they harbour are the natural heritage of this state and country. Learning about

them -- which species are present; which species are rare; why some are common

and some rare; the factors that control each species' occurrence; how each influences

the occurrence of other species -- enriches our lives.

While

most North American species of plants have been described, even in a state as

small as Iowa and with as few natural habitats remaining, we still are finding

previously undescribed species (albeit rarely), new state records for some (e.g.,

a population of Southern Adder's-tongue (Ophioglossum vulgatum L.) was

discovered in southeast Iowa in 1994, Horton unpublished data), and county records

for numerous species. And we have much to learn about the ecological role of

the species that occur here. The remnants of natural habitats and the biodiversity

they harbour are the natural heritage of this state and country. Learning about

them -- which species are present; which species are rare; why some are common

and some rare; the factors that control each species' occurrence; how each influences

the occurrence of other species -- enriches our lives.

In 1973, the United States Endangered Species Act provided federal protection for plants as well as animals, and in 1975, the Iowa Legislature passed the Endangered Wildlife and Plants Act (Iowa Acts and Joint Resolutions 1975), which required the following:

|

• The State Conservation Commission [presently the Natural Resource Commission] "shall perform those acts necessary for the conservation, protection, restoration, and propagation of endangered and threatened species...". •The Director of the State Conservation Commission [presently the Director of the Department of Natural Resources] "shall conduct investigations on fish, plants and wildlife in order to develop information relating to population, distribution, habitat needs, limiting factors, and other biological and ecological data to determine management measures necessary for their continued ability to sustain themselves successfully". |

|

• The Commission "shall review the state list of endangered and threatened species at least every two years and may amend the list". • The Director "shall establish programs, including acquisition of land or aquatic habitat, necessary for the management of endangered and threatened species". |

Subsequently, the

Management and Protection of Endangered Plants and Wildlife (Code of Iowa 1977)

mandated

preparation of a list of "fish, plants, and wildlife which are determined to

be endangered or threatened within the state". The Iowa Administrative Code

listings of Endangered and Threatened Plant Species, the first of which was

published in 1977, provide legal protection for rare species, and the lists

have proven crucial in preventing further destruction. For example, the Iowa

Department of Transportation was required to reroute the Highway 63 Bypass around

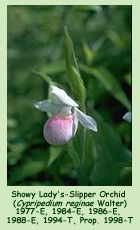

Eddyville because a population of the state threatened, Tubercled Orchid (Platanthera

flava (L.) var. herbiola (R. Br.) Luer) was discovered in the path

of the proposed bypass.

mandated

preparation of a list of "fish, plants, and wildlife which are determined to

be endangered or threatened within the state". The Iowa Administrative Code

listings of Endangered and Threatened Plant Species, the first of which was

published in 1977, provide legal protection for rare species, and the lists

have proven crucial in preventing further destruction. For example, the Iowa

Department of Transportation was required to reroute the Highway 63 Bypass around

Eddyville because a population of the state threatened, Tubercled Orchid (Platanthera

flava (L.) var. herbiola (R. Br.) Luer) was discovered in the path

of the proposed bypass.

To date, five lists of endangered and threatened species have been published in the Iowa Administrative Code, in 1977, 1984 and 1986 (the latter two are identical), 1988 and 1994, and a sixth was proposed in 1998, but subsequently cancelled in response to public protest (written comments submitted to the Iowa DNR). In addition, in 1998, a list of 'candidate' species was circulated with the proposed list. There also are three reports on endangered and threatened plants, from 1978 (Roosa & Eilers 1978), 1986 (Roosa, Pusateri & Eilers 1986) and 1989 (Roosa, Leoschke & Eilers 1989), that correspond to the Iowa Administrative Code lists of 1977, 1984-86, and 1988. Only vascular plants were included in the five published lists; however, the 1998 proposed list also incorporated mosses, hepatics (liverworts), fungi (mushrooms/toadstools) and lichens.

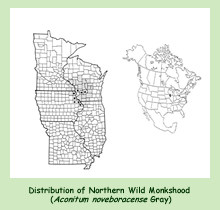

The

federal lists of endangered and threatened

species provide

a continental perspective. Their focus is on species that are rare if one considers

the country as a whole. Some of these species may be locally abundant at individual

localities or even in some states; Northern Wild Monkshood (Aconitum noveboracense

Gray) is one such species that occurs in Iowa. State lists are, by their very

nature, constrained to a provincial focus. Their role is at the local level.

The

federal lists of endangered and threatened

species provide

a continental perspective. Their focus is on species that are rare if one considers

the country as a whole. Some of these species may be locally abundant at individual

localities or even in some states; Northern Wild Monkshood (Aconitum noveboracense

Gray) is one such species that occurs in Iowa. State lists are, by their very

nature, constrained to a provincial focus. Their role is at the local level.

Five species are federally

listed, all as threatened. They are:

Northern Wild Monkshood (Aconitum noveboracense Gray)

Mead's Milkweed (Asclepias meadii Torrey ex Gray)

Prairie Bush Clover (Lespedeza leptostachya Engelm.)

Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid (Platanthera leucophaea (Nutt.) Lindley)

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Platanthera praeclara Sheviak & Bowles)

Three categories, endangered, threatened and special concern, are used in the Iowa Administrative Code lists, but only species designated endangered and threatened have legal protection in Iowa. Endangered and threatened are defined in Iowa as they are federally. The special concern category was introduced in the 1988 Iowa Administrative Code and provides no legal protection. It is not used in the federal listings. Two other categories, extirpated (including presumed and possibly extirpated) and undetermined, are used in at least one of the three Endangered and Threatened Plant reports (Roosa & Eilers 1978, Roosa, Pusateri & Eilers 1986, Roosa, Leoschke & Eilers 1989), but not the Iowa Code or federal lists.

The functional criteria

for determining whether a species will be included in the Iowa Administrative

Code

lists of endangered and threatened species are not given in the Code. It simply

is stated that "The natural resource commission, in consultation with scientists

with specialized knowledge and experience, has determined the following animal/plant

species to be endangered, threatened or of special concern" (Iowa Administrative

Code 1994). However, the primary criterion for the five Code plant lists published

to date (1977 through 1994) has been rarity; that is, species known from a limited

number of sites are listed.

Code

lists of endangered and threatened species are not given in the Code. It simply

is stated that "The natural resource commission, in consultation with scientists

with specialized knowledge and experience, has determined the following animal/plant

species to be endangered, threatened or of special concern" (Iowa Administrative

Code 1994). However, the primary criterion for the five Code plant lists published

to date (1977 through 1994) has been rarity; that is, species known from a limited

number of sites are listed.

The Code lists from

1977, 1984 and 1986 (the latter two are identical), and 1989 correspond to three

reports on rare plants by Roosa and Eilers (1978), Roosa, Pusateri and Eilers

(1986) and Roosa, Leoschke and Eilers (1989). All three contain distributional

information for each species, and the second and third include county

dot maps, with closed circles representing post-1950 records or extant occurrences

and open circles representing pre-1950 records or sites known to have been destroyed.

The dot maps are based on verifiable herbarium records, literature citations,

and also sight records (someone has seen the plant, but there is no specimen

record). Species designated endangered or threatened in these reports generally

are known from less than five extant sites (~=counties), although a few are

known from eight or nine because other factors were taken into consideration.

reports on rare plants by Roosa and Eilers (1978), Roosa, Pusateri and Eilers

(1986) and Roosa, Leoschke and Eilers (1989). All three contain distributional

information for each species, and the second and third include county

dot maps, with closed circles representing post-1950 records or extant occurrences

and open circles representing pre-1950 records or sites known to have been destroyed.

The dot maps are based on verifiable herbarium records, literature citations,

and also sight records (someone has seen the plant, but there is no specimen

record). Species designated endangered or threatened in these reports generally

are known from less than five extant sites (~=counties), although a few are

known from eight or nine because other factors were taken into consideration.

When the 1994 Code list was proposed in 1993, Dr. John Pearson of the Iowa Department

of Natural Resources (DNR) circulated a "Rationale for listing of plant species

as Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern" (J. Pearson in litt.

1993). Again, the primary criterion was rarity: if a species occurred in five

or fewer counties based on recent (post-1950) records, it would be considered

for listing . Dr. Pearson reported that 387 species met this criterion (as in

the rare plant reports cited above, in practice, some species considered for

listing actually were known from more than five counties); however, an additional

factor, 'Inventory Bias', also was taken into consideration. This was based

on the premise that general inventories of sites result in collection bias.

That is, species that are problematic taxonomically and those that occur in

'under-inventoried habitats', specifically, disturbed and aquatic habitats,

will be under-represented in collections. When species in these categories were

removed, a total of 151 species were left(J. Pearson in litt.

1993).

In the Code lists from 1977, 1984 and 1986, and 1989, a noteworthy exception

to the rarity criterion is that species listed as extirpated (also presumed

extirpated or possibly extirpated) in the rare plant reports (a total of 91

species in the three reports) are not included in the Code. These species are

included in the 1994 Code list; however, they are designated special concern,

so they have no legal protection if extant populations are found.

In

October of 1998, a fifth list of endangered and threatened plant species was

proposed, and Dr. Pearson

provided a discussion of selection criteria and a list of candidate species

(J. Pearson in litt. 1998). Although rarity was a fundamental criterion

for placing a species on the candidate list, additional criteria were applied

subsequently and these focused on 'natural habitats' and a 'regional perspective'.

Species that occur in disturbed habitats were excluded from consideration, on

the premise that disturbance-adapted species are more likely to persist. Species

that occur only

In

October of 1998, a fifth list of endangered and threatened plant species was

proposed, and Dr. Pearson

provided a discussion of selection criteria and a list of candidate species

(J. Pearson in litt. 1998). Although rarity was a fundamental criterion

for placing a species on the candidate list, additional criteria were applied

subsequently and these focused on 'natural habitats' and a 'regional perspective'.

Species that occur in disturbed habitats were excluded from consideration, on

the premise that disturbance-adapted species are more likely to persist. Species

that occur only in the outer two tiers of counties were excluded, because they are presumed

to be more common in adjacent states.

in the outer two tiers of counties were excluded, because they are presumed

to be more common in adjacent states.

This 1998 proposed list was cancelled in early 1999 in response to public protest

(written comments submitted to the Iowa DNR). Subsequently, Drs. Pearson and

Daryl Howell organized a "State Endangered Species Expert Workshop",

which was held on April 22, 1999. The Workshop was comprised of a series of

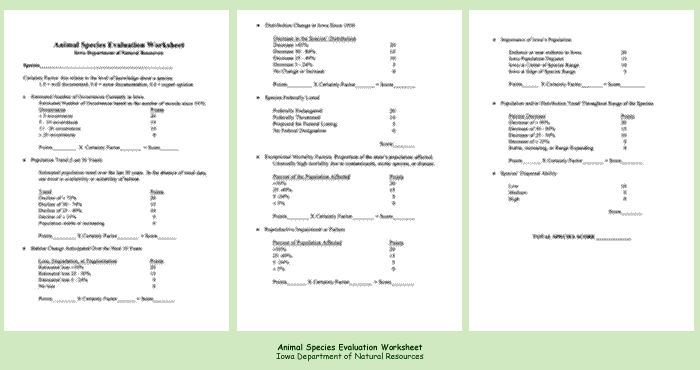

presentations, and a short question/discussion period. Subsequently (9/24/99),

Dr. Howell distributed a questionnaire (D. Howell e-mail, 9/24/99) to some specialists

in the state, soliciting assessment of a list of 22 criteria. A year later (D.

Howell e-mail, 9/18/00), he distributed an "Animal

Species Evaluation Worksheet" with ten criteria. Species are assigned

a score with respect to each criterion and the sum of these scores is used to

determine whether a species will be listed.

Further revisions

of the plant list have not been proposed; however, an amendment of the list

of animal species was  proposed

recently (October 2001). As with the 1998 proposed plant list, this amended

animal list is based on additional criteria, including "regional status, distribution

changes since 1930, estimated habitat changes in the next 10 years and population

trends" (Iowa DNR News, Natural Resource Commission, October 11, 2001). The

criteria used were those on the "Animal Species Evaluation Worksheet"

(see above), as well as "information and documentation of various experts"

(D. Howell e-mail, 3/6/02).

proposed

recently (October 2001). As with the 1998 proposed plant list, this amended

animal list is based on additional criteria, including "regional status, distribution

changes since 1930, estimated habitat changes in the next 10 years and population

trends" (Iowa DNR News, Natural Resource Commission, October 11, 2001). The

criteria used were those on the "Animal Species Evaluation Worksheet"

(see above), as well as "information and documentation of various experts"

(D. Howell e-mail, 3/6/02).

|

SOURCE

& CATEGORY |

IA

Adm. Code 1977 |

IA

Adm. Code 1984 |

IA

Adm. Code 1986 |

IA

Adm. Code 1988 |

IA

Adm. Code 1994 |

DNR

Prop. List 1998 |

| Endangered (E) |

100

|

123

|

123

|

140

|

64

|

16

|

| Threatened (T) |

52

|

56

|

56

|

58

|

89

|

93

|

| Special Concern (SC) |

|

|

28

|

227

|

167

|

|

| TOTAL E + T |

152

|

179

|

179

|

198

|

153

|

109

|

The number of listed species with legal protection (i.e., endangered and threatened) rose from approximately 150 in 1977 to nearly 200 in 1988, and then declined to 150 in 1994. One of the concerns regarding the list proposed in 1998 was that it would have further reduced the number of legally protected species to just over 100.

The law (as specified in the Iowa Acts and Joint Resolutions 1975) requires that the endangered species lists shall be reviewed at least every 2 years; however, reviews have been conducted irregularly and less frequently (1977, 1984, 1986, 1988 and 1994).

• The purpose of the state lists should be to focus at the local level and provide protection for any rare species, even though some of these species may be more abundant or even common in other parts of the country. Clearly, that is the intent of the Iowa endangered species legislation, which is to protect species "determined to be endangered or threatened within the state" (Code of Iowa 1977). Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea (L.) Miller) is an example of a species that is rare in Iowa, but relatively widespread and common in parts of Minnesota and Wisconsin.

• Considering how little we have left in Iowa, we should err on the side of caution. If there is any possibility that a species is rare, it should be given legal protection until proven otherwise; the onus should be on demonstrating that a species is not at risk, not that it is. Examples include such aquatics as one of the Duckweeds, Lemna perpusilla Torrey, and a Bur-reed, Sparganium androcladum (Engelm.) Morong. Both are known only from one or two sites, yet on the 1994 Iowa Code list, they are designated Special Concern, a category that gives no legal protection, and they were not on the 1998 DNR Proposed List.

• Endangered species lists should have a sound scientific basis. In the past, herbarium specimens, literature citations, and sight records have been the sources for the Iowa lists. However, only specimens, preserved samples of living organisms, can be evaluated. Scientists or knowledgeable laypersons

can examine collections to determine whether the original identification is correct. A sight record, even from a knowledgeable individual, cannot be evaluated. Also, species concepts change over time and what was thought to be a single species might later be recognized as two. This situation is exemplified by the two federally listed orchids, the Eastern (Platanthera leucophaea (Nutt.) Lindley) and Western (Platanthera praeclara Sheviak & Bowles) Prairie Fringed Orchids. Until 1986, they were recognized as a single species with the former Latin name, but Sheviak and Bowles (1986) presented evidence that they represent a pair of cryptic or sibling species, the distinction between them having been overlooked. If pre-1986 records of these species were based only on sight records, it would be impossible to trace which of the two had been at each locality, because most of the sites have been destroyed, the populations long extinct. The only record of what was present are specimens.

• Rarity must be the fundamental criterion. However, how should that be assessed? Number of counties? Number of sites? Number of individuals? Considering that Iowa has been settled

since the early- to mid-1800s, it is astonishing how incomplete our data on plants are. This simply reflects the dearth of expertise. Historically, there have been relatively few individuals with the knowledge and training to provide scientific documentation (make collections) of Iowa plants, and there may be fewer today. Generally, these people have been scientists with positions in academic institutions or museums where there are herbaria; however, over the last forty or fifty years, the emphasis in biology has shifted away from field studies towards laboratory-based, molecular studies. As a result, our knowledge of the species that occur in Iowa is woefully incomplete. For example, a new species of Prairie Moonwort (Botrychium campestre Wagner & Farrar) was described in 1986 (Wagner & Wagner 1986), new state records still are being discovered (e.g., a disjunct population of another small fern, Wall Rue (Asplenium ruta-muraria L.), was discovered recently in eastcentral Iowa, Cady & Horton 2004), and new

county records are commonplace. Most state parks, state preserves, and wildlife areas never have been thoroughly inventoried for plants. Thus, at the present time, we can assess rarity on the basis of county records, or at best, number of sites.

There is a desperate need for intensive inventories, documented by herbarium specimens, of the remaining natural areas in Iowa, particularly on public lands, to give us a more accurate idea of which species are present and the number of sites at which they occur. Recently, the Iowa State Preserves Board and also the Iowa DNR have taken positive steps towards this goal by providing funding for inventories of state preserves, as well as other public and private lands. Equally pressing is the need for entry of specimen data into a database, so that data on distribution, number of sites and date of collection are readily accessible. It is difficult to estimate the number of species of vascular plants that should be listed as either endangered or threatened, but an accurate list of candidate species cannot be generated until all Iowa specimen records are available electronically. The University of Iowa Herbarium has developed a database in Access for this purpose and is just beginning a project to database all Iowa collections data. These data, including distribution maps for each species, will be made available electronically via this website.• Should factors other than rarity be taken into consideration? On the surface, the introduction of additional criteria, as has been done recently (see "Animal Species Evaluation Worksheet") for the listings of animals, appears to give the assessment greater validity, and most of these criteria could, at least in theory, be applied to plants. However, even for criteria that, on the surface, appear to address the central issue of rarity in greater detail (for example population trends, and distribution changes in Iowa over the last 70 years), in many instances the effect will be to dilute the importance of rarity. For example, if populations appear not to have declined and distributions not to have shrunk, a rare species will be assigned a low score for both criteria, making it less likely that the overall score will be sufficiently high that it will be listed. Also, for many, if not most, rare plants, we simply don't have data on population trends. Another criterion is whether a species is federally listed. Why give extra points to species that are federally listed? They have federal protection, which ensures they have protection within the state. Once again, this dilutes the significance of rarity in Iowa for the majority of species that are rare in this state, but not federally listed. Two other criteria, 'Importance of Iowa's Population' and 'Population and/or Distribution Trend Throughout Range of the Species', are contrary to the intent of the Iowa endangered species legislation, to protect species "within the state" (Code of Iowa 1977). The Importance of Iowa's Population is assessed from the perspective that a species on the edge of its range in Iowa is scored lower because it occurs elsewhere. Consideration of Population and/or Distribution Trends throughout the range of a species similarly takes the focus away from the local, state level where it belongs. Both criteria are a replay of the controversial 'regional perspective' that was introduced with the 1998 proposed list. Devaluing species that are on the edge of their range in Iowa also fails to consider that such populations can harbour greater genetic variability and/or may differ genetically from populations in the centre of the range. Such populations may be critical in determining survival of species in response to climate change.

Overall, additional criteria are detrimental because they deflect the focus and dilute the importance of rarity in the evaluation. It is essential that the focus be kept where it belongs: if a species is rare in Iowa, it potentially could become extinct in this state and should be listed. Data on population trends, both within and outside of this state, and distribution changes over time, should be gathered with a view towards monitoring the status of rare species, not determiningwhether or not they should be listed.

• Species believed extirpated in Iowa must be listed as either endangered or threatened, so they have legal protection if extant populations are discovered. Of the 91 species given this designation in the rare plant reports (Roosa & Eilers 1978, Roosa et al. 1986, and Roosa et al. 1989), extant populations of at least one-third have been discovered subsequently. For example, the Green Fringed Orchid, Platanthera lacera (Michx.) G. Don ex Sweet, is listed as Presumed Extirpated by Roosa, Leoschke and Eilers (1989), but a population was discovered in southeast Iowa in 1994 (Horton, unpublished data).

• In a few instances

once-common species are being harvested to the point of extinction because they have economic value. A good example of this is Ginseng (Panax quinquefolia L.). As in many other states in the eastern U.S. where Ginseng has become very rare, harvest permits are available from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources for a fee of $10 per year. Not only should permits not be offered, this species needs to be given legal protection.

• All groups of plants and plant-like organisms, not just the vascular plants, must be included on the endangered species lists. The mosses, hepatics (liverworts) and hornworts, which are true plants, nevertheless respond quite differently than vascular plants to some ecological factors, and species diversity in the two groups does not necessarily correlate in different habitats. However, including additional groups of organisms on the lists should not entail reducing the numbers of species in groups already included.

• Regrettably, it is unrealistic to expect that endangered and threatened Iowa plant species will 'recover' as the Bald Eagle has nationally. In Iowa, more and more habitat is being destroyed, more and more alien species are running amok. Not only are the numbers of endangered and threatened species almost certainly going to increase, a plausible estimate of the number of vascular plants that should be listed presently is about 300-500 species.

Bishop, R.A. 1981. Iowa's wetlands. Proc. Iowa Acad. Sci. 88: 11-16.

Bishop, R.A., J. Joens & J. Zohrer. 1998. Iowa's wetlands, present and future with a focus on prairie potholes. J. Iowa Acad. Sci. 105: 89-93.

Bishop, R.A. & A.G. van der Valk. 1982. Wetlands, pp. 208-229. In T.C. Cooper (executive ed.) & N.S. Hunt (associate ed.), Iowa's Natural Heritage. Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation, Des Moines, Iowa. 341 pp.

Cady, T.F. & D. Horton. 2004. Asplenium ruta-muraria L. in Iowa. Am. Fern J. 94: 30-32.

Code of Iowa. 1977. Management and Protection of Endangered Plants and Wildlife, Chapter 109A. pp. 625-626.

Eilers, L.J. & D.M. Roosa. 1994. The Vascular Plants of Iowa. University of Iowa Press, Iowa City, Iowa. 304 pp.

Iowa Acts and Joint

Resolutions. 1975. Endangered

Wildlife and Plants, H. F. 497. Laws of the

Sixty-sixth General Assembly, 1975 Session, Chapter 109. pp. 260-262.

Iowa Administrative Code. 1977. Endangered or Threatened Plants and Animals. Conservation [290], Chapter 19. 9 pp.

Iowa Administrative Code. 1984. Endangered or Threatened Plants and Animals. Conservation [290], Chapter 19. 10 pp.

Iowa Administrative Code. 1986. Endangered and Threatened Plant and Animal Species. Natural Resource Commission [571], Chapter 77. 10 pp. Iowa

Administrative Code. 1988. Endangered and Threatened Plant and Animal Species. Natural Resource Commission [571], Chapter 77. 14 pp.

Iowa Administrative Code. 1994. Endangered and Threatened Plant and Animal Species. Natural Resource Commission [571], Chapter 77. 13 pp.

Jungst, S.E., D.R. Farrar & M. Brandrup. 1998. Iowa's changing forest resources. J. Iowa Acad. Sci. 105: 61-66.

Kartesz, J.T. 1999. A Synonymized Checklist and Atlas With Biological Attributes for the Vascular Flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland. First Edition. In: Kartesz, J.T. and C.A. Meacham. Synthesis of the North American Flora, Version 1.0. North Carolina Botanical Garden, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Kartesz, J.T. & C.A. Meacham. 1999. Synthesis of the North American Flora, Version 1.0. North Carolina Botanical Garden, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Lewis, D. Q. 1998. A literature review and survey of the status of Iowa's terrestrial flora. J. Iowa Acad. Sci. 105: 45-54.

Norris, W.R., D.Q. Lewis, M.P. Widrlechner, J.D. Thompson and R.O. Pope. 2001. Lessons from an inventory of the Ames, Iowa, Flora (1859-2000). J. Iowa Acad. Sci. 108: 34-63.

Prior, J.C. 1991. Landforms of Iowa. University of Iowa Press, Iowa City, Iowa. 153 pp.

Pusateri, W.P., D.M. Roosa & D.R. Farrar. 1993. Habitat and distribution of plants special to Iowa's Driftless Area. J. Iowa Acad. Sci. 100: 29-53.

Roosa, D.M. & L.J. Eilers. 1978. Endangered & Threatened Iowa Vascular Plants. Special Report No. 5, State Preserves Advisory Board, State Conservation Commission, Wallace State Office Building, Des Moines, Iowa. 91 pp. + Appendix C.

Roosa, D.M., W.P. Pusateri & L.J. Eilers. 1986. Distribution of Endangered and Threatened Iowa Plants. Special Report No. 6, State Preserves Advisory Board, State Conservation Commission, Wallace State Office Building, Des Moines, Iowa. 94 pp. + appendices.

Roosa, D.M., M.L. Leoschke & L.J. Eilers. 1989. Distribution of Iowa's Endangered and Threatened Vascular Plants. Iowa Department of Natural Resources. 107 pp. + appendices.

Sheviak, C. & M.L. Bowles. 1986. The prairie fringed orchids: a pollinator-isolated species pair. Rhodora 88: 267-290.

Smith, D.D. 1998. Iowa prairie: original extent and loss, preservation and recovery attempts. J. Iowa Acad. Sci. 105: 94-108.

Wagner, W.H. & F.S. Wagner. 1986. Three new species of moonworts (Botrychium subgenus Botrychium) endemic in western North America. Am. Fern J. 76: 33-47.

Wilson, E.O. 1992. The Diversity of Life. W.W. Norton & Company, New York. 351 pp.

The first list of endangered and threatened plants (Iowa Administrative Code 1977) included 152 species of vascular plants, 100 of which were classified as endangered and 52 as threatened. In a companion report, Endangered & Threatened Iowa Vascular Plants, Roosa and Eilers (1978) provided a more extensive list of 246 species and recognized four additional categories. Their list included 101 endangered species, 51 threatened, 2 extirpated, 64 presumed extirpated, 3 possibly extirpated, and 25 undetermined. With respect to endangered and threatened species, the companion report and the Iowa Administrative Code lists are virtually identical (one species treated as threatened in the latter is given as endangered in the former); however, there is no mention in the Code of the 69 rarest species, those identified in the companion list as extirpated (including presumed extirpated and possibly extirpated), nor of the 25 listed as undetermined. The designations endangered and threatened are not defined in the 1977 Iowa Administrative Code, but in both the 1975 Iowa Acts and Joint Resolutions, and the 1977 Code of Iowa, endangered species are "any species...which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant part of its range", and Threatened species are "any species which is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range". More functional definitions for these two categories, as well as the additional ones, are given in the companion report (Roosa & Eilers 1978). Endangered species generally are known from three or fewer sites; threatened species have a very limited distribution; extirpated species no longer occur in the state; and undetermined species are of concern, but there is insufficient information on their status. Roosa and Eilers (1978) also noted that the category assigned might be modified in consideration of other such factors as the degree of protection of sites (e.g., species occurring on state preserves have maximum protection) and the status of the habitat in which species occur (e.g., some habitats are at greater risk).

A second list of endangered and threatened species was published in the Iowa Administrative Code in 1984 and again in 1986. It included 123 endangered and 55 threatened species of vascular plants for a total of 178. The 1986 companion report, Distribution of Endangered and Threatened Iowa Plants, by Roosa, Pusateri and Eilers (1986) included county distribution maps for 123 endangered species, 56 threatened, 49 presumed extirpated, and 33 special concern (the latter were designated undetermined in the 1978 report; see above), for a total of 261. Again, 49 of the rarest species, those presumed extirpated, were not included in the Iowa Administrative Code lists. The distribution maps in the companion report were reportedly based on published records, personal observations and herbarium specimens, with open and closed circles used to differentiate between pre- and post-1950 records, respectively.

A third endangered and threatened species list was published in 1988 (Iowa Administrative Code 1988) and included 140 endangered species, 58 threatened, and 29 special concern for a total of 198 endangered and threatened. Definitions of the categories are included in this list, with endangered and threatened species defined as they are in the 1975 Iowa Acts and Joint Resolutions, and the 1977 Code of Iowa, while the designation, special concern, is for "any species about which problems of status or distribution are suspected, but not documented". It also is noted that special concern species have "no special protection under this rule"; in other words, unlike endangered and threatened species, those designated special concern have no legal protection. The companion report, Distribution of Iowa's Endangered and Threatened Vascular Plants, by Roosa, Leoschke and Eilers (1989) documented the county distributions (prior, and subsequent to 1950) of 137 endangered species, 58 threatened, 45 presumed extirpated, and 29 special concern, for a total of 269. As in previous Iowa Administrative Code lists, the 45 species presumed extirpated are not included.

In 1994, the fourth list of endangered and threatened species (Iowa Administrative Code 1994) included 64 endangered species, 89 threatened, and 229 special concern (the latter figure excludes four species listed in error based on a draft manuscript of Eilers and Roosa (1994), pers. comm. John Pearson), for a total of 153 endangered and threatened. A "Rationale for listing of plant species as Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern" was circulated by Dr. John Pearson (in litt. 1993) of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources when this list was proposed in October of 1993. The criteria he identified included origin - alien species were excluded; statewide abundance and distribution - in general, candidates for the list were selected from those designated 'rare' in The Vascular Plants of Iowa by Eilers and Roosa (1994) and occurring in five or fewer counties based on recent (post-1950) records; inventory bias - taxonomically difficult species like Carex (sedges) and Crataegus (hawthorn), and species occurring in habitats thought to be under-inventoried (e.g., disturbed and aquatic habitats) were designated Special Concern; and degree of protection - species occurring on protected land, including parks, preserves, Iowa DNR wildlife areas, county conservation board lands, and properties of The Nature Conservancy or other recognized conservation agencies were classified as threatened, while those not present on such lands were endangered. It was noted that species presumed extirpated were listed as special concern, whereas they had not been listed previously.

A fifth list of endangered and threatened species was proposed in October of 1998. It included vascular plants (16 endangered, 92 threatened, and 168 special concern, for a total of 108 endangered and threatened); mosses (3 endangered, 25 threatened and 28 special concern, for a total of 28 endangered and threatened); hepatics (liverworts) (7 threatened and 6 special concern, for a total of 7 endangered and threatened); lichens (1 special concern, and none endangered and threatened); and fungi (3 special concern, and none endangered and threatened). A discussion of selection criteria and a list of candidate species were provided by Dr. John Pearson of the Iowa DNR (Pearson in litt. 1998).

The list proposed in 1998 differed from all previous lists in three respects: selection criteria emphasized 1) 'natural habitats' and 2) a 'regional perspective', and 3) nonvascular plants were included (see above). The rationale for emphasizing natural habitats was, species that occur only in such habitats are most vulnerable to the impact of human disturbance, whereas disturbance-adapted species are more likely to persist. An additional consideration was that disturbed habitats tend to be under-inventoried. With respect to the regional perspective, it was argued that the extra-Iowa distribution of species should be taken into consideration. Thus, federally listed species (endangered, threatened or species at risk) "were classified as Endangered … if they occurred in natural habitats or as Special Concern if they occurred in disturbed habitats". Species not federally listed "were classified no higher than Threatened". A second aspect of the regional perspective was that the emphasis in listings was on 'interior' species; that is, those that were "typical of the original, widespread flora of the state and … have become rare through loss of habitat". In contrast, 'peripheral' species, that is, those that are "typical of surrounding states and … occur in Iowa only as minor range extensions", were excluded. Functionally, 'peripheral' species were those that occurred only in the outer two tiers of counties. The candidate list, that is, an enumeration of species from which those on the proposed list were selected, included 538 species of vascular plants, 134 mosses, 33 hepatics, 1 lichen, and 3 fungi, with annotations on habitat (natural vs. disturbed); Iowa distribution (interior vs. peripheral); federal status; status in at least one neighbouring state; post-1950 records; adequacy of documentation; indication of taxonomic difficulty or problems with geographic range; status on the 1994 list; and proposed status. Among the vascular plants on the candidate list, 151 were not included on any of the lists previously published in the Iowa Administrative Code. The proposed list was cancelled in January of 1999 in response to public protest, which focused mainly on the 'regional perspective' criterion. It was pointed out that eliminating species that occurred only in the outer two tiers of counties would exclude nearly two-thirds of the surface area of Iowa, as well as four landform regions, the Paleozoic Plateau, the Mississippi and Missouri Alluvial Plains, and the Loess Hills (Prior 1986), the first and last of which include some of the biologically diverse regions of the state.

Last Updated: 03/14/2006